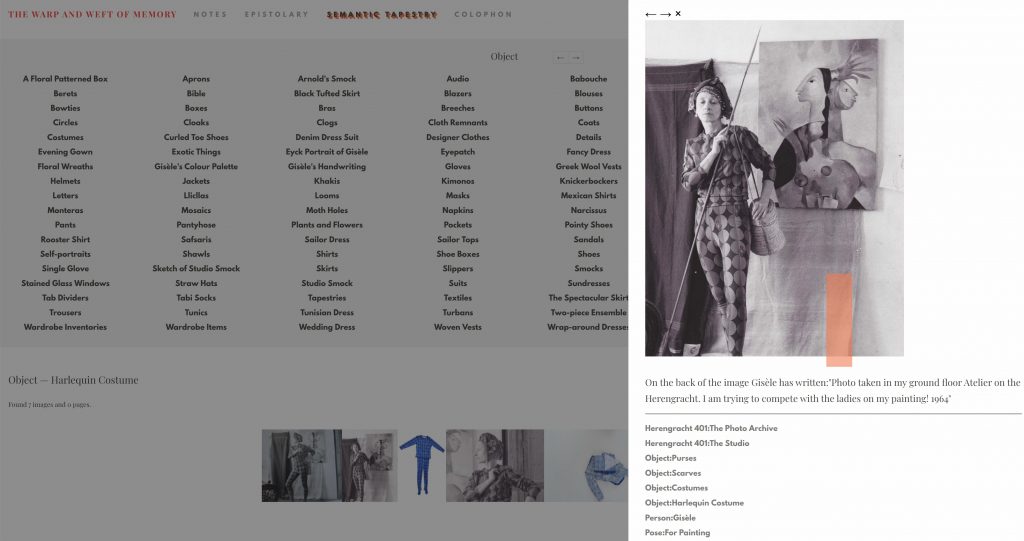

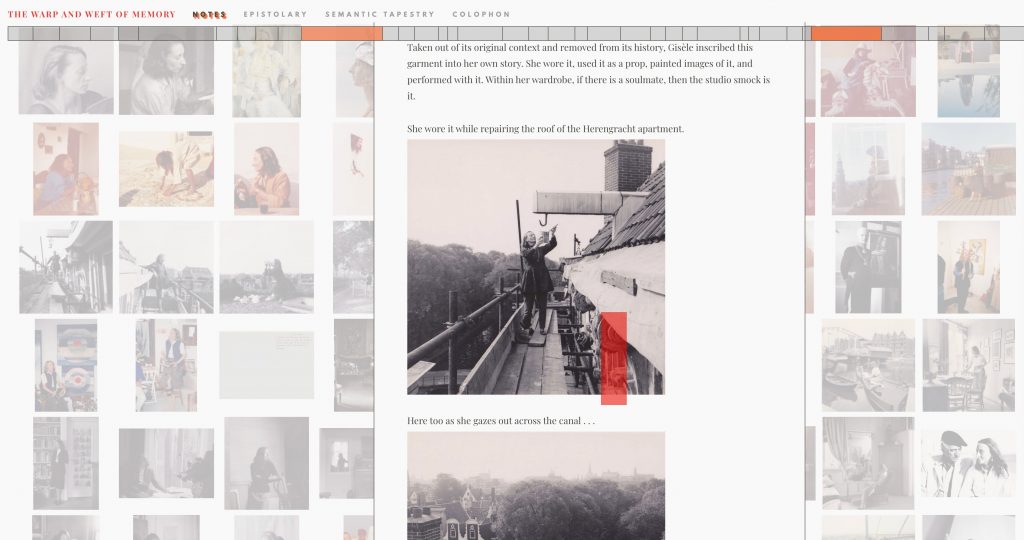

Our Content Editor, Amy Pickles, talks to RASL Researcher Renée Turner about her project The Warp and Weft of Memory. From September 2016 to September 2018 Renée worked at Castrum Peregrini, Amsterdam. Her research began in the wardrobe of Dutch artist Gisèle d’Ailly van Waterschoot van der Gracht, and worked through ways in which her life, work, and histories are found in textiles and clothing. Done with a team of people, her research resulted in public talks, an exhibition, a publication and an online narrative archive, which weaves connections to the present from a personal perspective.

Research Interview: Renée Turner

Amy Pickles: To me, your website exists like a digital wardrobe, I can nip around in and out of links and clicks. It reminds me of riffling through my own clothes when getting dressed – unable to choose, making pairings / connections and discarding them for something else. I reach the Do Not Forget tab, where you have linked a selection of images with the words;

Do not forget that you fed the pigeons in Piazzo san Marco

Do not forget the leaking pipe in winter

Do not forget the Ouzo that was once poured

I feel like forgetting is the warp and memory can be the weft of your project. They are both active in your process as well as what you are questioning. Could you talk a little about how to conduct research that includes forgetting? It seems immediately contradictory, but can there be more space for not knowing in research where you let something go, or travel by itself?

Renée Turner: There is that wonderful quote from Chris Marker’s San Soleil: “I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining.” Remembering and forgetting are connected activities and somehow my research needed to accommodate that tension. You know, one of the things I like about writing in a digital environment is that there is no master narrative, only tentative propositions, networked connections that can be followed or ignored. Maybe as a form, it suits my own inability to prioritise and make decisions and my desire to circle around things without really landing on a single point or conclusion. In this, I feel a connection to Gisèle – admittedly perhaps more projected than real.

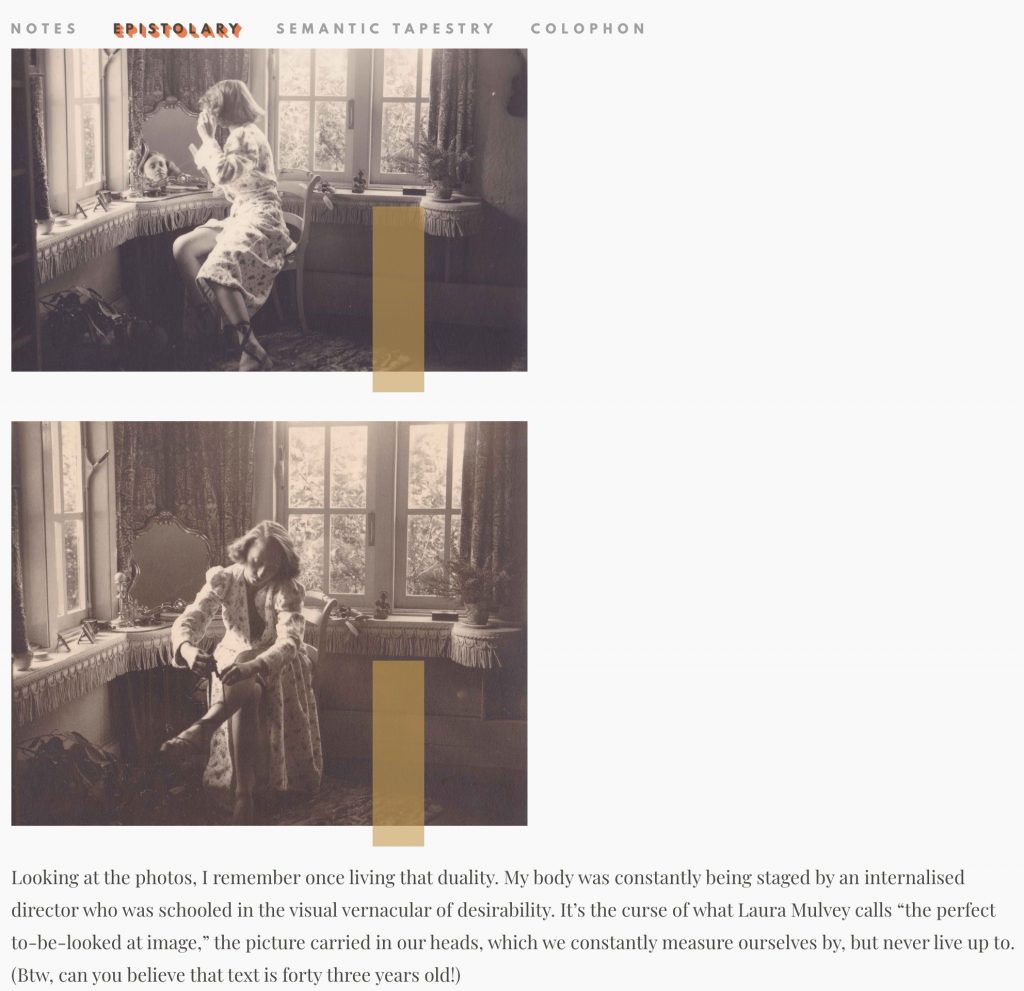

I was struck by Gisèle’s own writing that is both literally and figuratively all over the place. And by that I don’t mean her small books of poetry. That sanctioned writing, which declares itself as writing, was of no interest to me. For sure that’s no reflection on either its validity or relevance. But I was struck by all of her notes scattered throughout her studio, in her living room and tucked away in her closet. These scraps, woven throughout the physical space of Herengracht 401 are to my mind a form of lifewriting. Notes are considered marginalia but never the substance. So I was interested in that accumulation of marginalia – her pantyhose which are all neatly stored in a box, her endless closet inventories tucked away in an envelope and her photo archive with its various scribbles and filing systems. In these details and traces, Gisèle was trying to remember, but also struggling to not forget.

AP: When I travel through the printed publication – a newspaper style fold out on a2 paper (with the option to turn each page into a poster detailing a wonderful garment or fantastical scene) you include the categories within the publication itself, they form the way the writing is structured. This is fun to encounter as a reader, because it is a glimpse into your thinking out of linear structure, which is typically the way information is presented to us if we want to learn it.

In a novel, generally, you move through time at the pace of the story – the beginning is the start and you finish at the end. In an academic text you build towards a final statement, you follow the argument by learning at the start.

Has this process changed the way you think about the structure of how to research?

RT: I’ve always been interested in semantics and aggregation and what that combination brings to storytelling. This is what the digital affords – the capacity to view, and therefore narrate from different perspectives. It is a logic harkening back to the work of Aby Warburg and his Mnemosyne Atlas and Andre Malraux’s reconfigurable Le Musee Imaginaire. But I also see a relation to the kind of writing of Lydia Davis when she writes about observing a small group of cows in the pasture in front of her house. The cows are a fixed dataset, and through that restriction, the infinite presents itself through the ritual of re-describing. In other words, it’s the ethos of “let’s look at it this way, and that way, but also that way too”. So, it’s certainly possible within more traditional forms of writing, but I’ve always felt more at home working within digital environments.

AP: Your project has included moments of sharing and learning for the public, with a series of related lectures, presentations and discussions. As an educator, artist and researcher, do you make a distinction between each, and if so how?

RT: I don’t make a distinction between the different hats I wear – meaning as an artist, researcher or educator. Of course the frame of each is unique – formal education, public events or exhibitions have their own dynamic, expectations, limits and possibilities. But I have certainly tried to mix these registers to a varying degree.

AP: Is it important to infuse each practice with the other, like when I can use a footnote to learn of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Feminist Manifesto in your Epistolary (relating to a letter) and Mary Shelley in another.

RT: Knowledge is beholden. I’m a firm believer in acknowledging those who enrich and sharpen my thinking. We’re constantly building on the shoulders of others. With references, I situate myself in a collective and shifting body of knowledge – a mix of feminist, queer and non-Eurocentric perspectives that keep me humbled and conscious of the limits of what I know. It’s about studying and learning without mastering. References do not prove or bolster my position, instead they are outward pointing sign posts.

The Warp and Weft of Memory continues to live as an extensive MediaWiki closet. Scroll and click through it to unravel stories and non linear thoughts.

The Warp and Weft of Memory involved a team of people.

Illustrations: Cesare Davolio who is a tutor WdKA.

Frontend Interface Design: Ricardo Lafuenta (Piet Zwart Alumnus) and Ana Carvalho (Manufactura Independente)

Backend MediaWiki Design: Andre Castro who is tutor at the WdKA and Cristina Cochior who is a Piet Zwart alumna.

The project is funded by the Mondriaan Fund and Creative Industry Funds.

All images from Gisèle’s archive are courtesy of Castrum Peregrini and cannot be reproduced without permission.

Thank you to Renée, Gisèle and all others involved in the project.